You’ve probably heard Gymnopedie No. 1 by Erik Satie. While the piece has been around since 1888, I never noticed it until my piano teacher opened to its page in the repertoire book and got my attention by telling me that after Satie died, they entered his apartment to find three grand pianos stacked on top of each other. I’ve always liked playing pieces in minor keys that drag on with slow, swelling tension, and so my love for Gymnopedie No. 1 seems inevitable in hindsight. But initially, the story about his bizarre musical innovation stuck with me more than the piece itself did, and was my motivation for practicing. (NOTE: Shortly after this article was originally posted I learned that they actually only found two grand pianos. Only slightly less weird.)

Gymnopedie No. 1 is deceptively simple. It was literally written to be background music. It’s aged into the public domain, fulfilling its purpose of being present but barely noticeable. My teacher referred to the Trois Gymnopedies (Satie wrote three pieces named Gymnopedie in total) as “furniture music.” Others consider them to be the ancestor of modern ambient music. While Satie himself was relatively uninterested in technological or cultural advancement, he nonetheless set the stage for a completely new sound.

Unlike many pieces at the time that were intended to directly entertain, Satie put time towards writing music that people would hear, but not listen to. Trust me, once you can recognize the lilting melody of Gymnopedie No. 1, you’ll hear it when you least expect it (it’s like the Garfield effect). I was shocked to boot up my friend Violet’s video game, Every Letter, and hear its familiar haunting melody on the loading screen. I think the piece, arguably Satie’s magnum opus, has even become a TikTok sound.

It’s hard to explain what a “Gymnopedie” is. It isn’t a traditional style of music, but weirdly, the name serves a similar function to the titles of classical pieces. Musical compositions, regardless of instrument, were often titled with the kind of dance that would accompany them. Like a Waltz or Minuet, the Gymnopedie is related to a type of dance. But as the definition (found in Peter Lichtenthal’s Dictionnaire de Musique) clarifies, this dance is uniquely performed in the nude.

Wood engraving from William Smith’s (1813-1893) Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. PD-US-expired.

The word “Gymnopedie” is derived from Gymnopaedia, a Spartan coming-of-age festival featuring high-energy dances performed by groups of young, adult, and elderly men. Although the dynamic movement in extreme heat highlighted Gymnopaedia as a test of physical endurance for the young men, proving their masculinity, it also reinforced Spartan community values and bonds.

Now that we’ve taken a brief detour from a genre-inspiring piece into ancient Spartan coming-of-age rituals, let’s turn to the composer of the Trois Gymnopedies, Erik Satie, the Father of Furniture Music. Satie did more than compose a piece referencing Gymnopaedia—he personally identified as a “Gymnopedist.”

And that brings us to the question I’ve had for years: What is a Gymnopedist? What does it mean to try and personify, in one’s behaviors, ideologies, and habits, the character of a lively Spartan ritual celebrating transitions?

I’d argue that Satie’s identification as a Gymnopedist partially references the “coming of age” aspect of Gymnopaedia. Satie took on an unusual amount of distinct aesthetic eras over his 59 years of life, and I can only imagine that he enjoyed fresh starts, if not the entire process of rebirth.

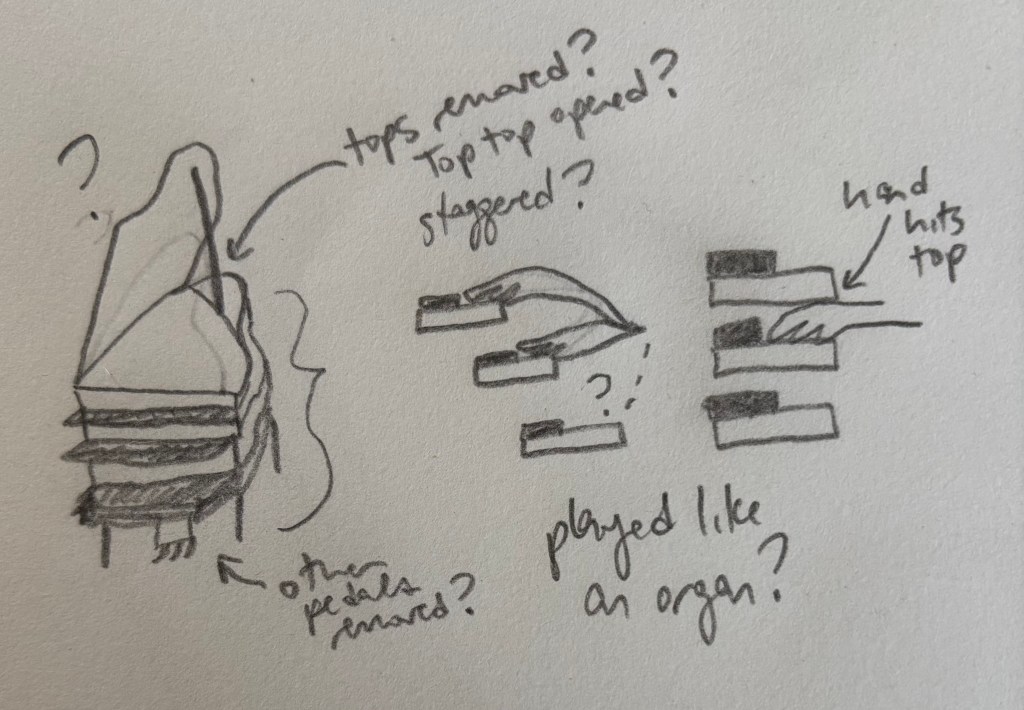

During one period, he carried a hammer with him everywhere he went. He had a period where he embodied the Bohemian aesthetic. He founded the Eglise Metropolitane d’Art de Jesus Conductor—a religion with one member (him)—during his years as a “priest;” nothing became of this religion, and in the Gymnopaedic spirit of rebirth, he ended what would come to be known as his “mystic period” to embrace velvet eccentricity. His final aesthetic era was marked by a bougie bowler hat, a wing collar, and the constant presence of an umbrella on his arm. After his death, they found (in addition to the three grand pianos) 100 umbrellas in his apartment, presumably to ensure he was never without such a critical part of his look.

Complimenting the spirit of transformation, the other aspect of the Gymnopaedia that Satie might have connected with identifies the Gymnopedist as a spectacle. Ancient people traveled from all over to witness the Gymnopaedia, even those who had no connection to the performers. Do the Spartan men transition to the next stage of their lives unless the crowd witnesses them do so? What’s the point of the effort put into meaningful change if no one recognizes it?

The act of creation itself isn’t necessarily a massive spectacle. The creator views their creation, but Satie shows us that a greater creative spectacle happens when something is viewed by the world, and is what keeps us interesting. We do not have to be spectacles—but in the spirit of authenticity, of embracing change, and celebrating ourselves—we can choose to be.

Prendergast, Mark. “The Ambient Century: From Mahler to Moby.” The Evolution of Sound in the Electronic Age. page 6. ISBN 0-7475-5732-2

Lichtenthal, Peter. 1839. “Gymnopedia.” Dictionnaire de Musique, Vol. 1 A–J. Translated by Dominique Mondo. Paris: Au Bureau de la France Musicale. p. 496.

Powell, Anton; Flower, Michael A. 2018. “Spartan Religion.” A Companion to Sparta. pp. 425–451. ISBN 978-1-4051-8869-2. OCLC 1029549436.

Christesen, Paul; Donald, G. Kyle. 2014. “Sport and Society in Sparta”. A Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity. ISBN 978-1-118-61004-6. OCLC 1162072582.

Leave a reply to Here I Am, But Who Are You? – Vincent Boone-Banko Cancel reply